China has become an increasingly significant player in the Middle East in the past decade. While it is still a relative newcomer to the region and is extremely cautious in its approach to local political and security challenges, the country has been forced to increase its engagement with the Middle East due to its growing economic presence there. At a moment when the United States’ long-standing dominance over the region shows signs of decline, European policymakers are increasingly debating the future of the Middle Eastern security architecture – and China’s potential role within that structure.

However, many policymakers have little knowledge of China’s position and objectives in the Middle East, or of the ways in which these factors could affect regional stability and political dynamics in the medium to long term. Given that China’s rise has led to intensifying geopolitical competition in Europe’s neighbourhood, European policymakers should begin to factor the country into their thinking about the Middle East.

China’s relationship with the Middle East revolves around energy demand and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013. In 2015, China officially became the biggest global importer of crude oil, with almost half of its supply coming from the Middle East. As a strategically important crossroads for trade routes and sea lanes linking Asia to Europe and Africa, the Middle East is important to the future of the BRI – which is designed to place China at the centre of global trade networks. For the moment, China’s relationship with the region focuses on Gulf states, due to their predominant role in energy markets.

The cooperation framework outlined in two key Chinese government documents focuses on energy, infrastructure construction, trade, and investment in the Middle East. They barely mention security cooperation – in line with Beijing’s narrative that its involvement in the region does not advance its geopolitical goals. Beijing is careful to avoid replicating what it sees as Western intervention and puts forward a narrative of neutral engagement with all countries – including those that are at odds with each other – on the basis of mutually beneficial agreements. China has a vision of a multipolar order in the Middle East based on non-interference in, and partnerships with, other states – one in which the country will promote stability through “developmental peace” rather than the Western notion of “democratic peace”.

However, Beijing will likely struggle to maintain its neutral narrative as Chinese interests in the volatile region grow. This will be especially true if the US speeds up its apparent withdrawal from the Middle East, a trend that is likely to force China to protect these interests itself. China may not want to strengthen its political and security presence in the region – but it may feel that it has no choice in the matter. Meanwhile, China’s deepening engagement with countries on both sides of fierce rivalries could drag it into disputes unrelated to its core objectives. While it is apparently happy to maintain a more distant role for the moment, China is already showing initial – albeit still small – signs of deepening political and security involvement in the Middle East. It remains to be seen how far the country will take this, and to what end goal.

In the face of inconsistent policies from the US and with an eye to a future with greater Chinese power and influence, leaders in the Middle East have been receptive to Chinese outreach so far. The BRI addresses their domestic development concerns and, at the same time, signals Beijing’s intention to become more invested in the region. This comes at a moment when Western countries, particularly the US, suffers from Middle East fatigue. At this stage, it is hard to determine whether this is merely a hedging strategy designed to diversify their extra-regional power partnerships or if it signals the beginning of a realignment that stretches across the Middle East to east Asia. It is clear, however, that China will be an engaged partner with a clearly articulated approach to building a stronger presence in the region.

Beijing has a negative view of the Western practices of alliance politics, spheres of influence, and economic sanctions. It is wary of the concept of the responsibility to protect, opposes regime change, and dismisses the argument that some governments in war-torn MENA countries are evil or are troublemakers. Beijing stresses that all MENA states are partners in a dialogue on inclusive and comprehensive solutions to conflicts. China attempts to burnish its world power status by upholding these standards.

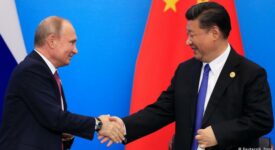

As a rising power, China engages with MENA in experimental and preliminary ways that are devoid of a clear strategy. The ruling party aims to increase its popularity at home rather than seek a geopolitical rivalry with the US in MENA. It does so by maintaining stable great power relations and expanding its commercial interests across MENA. Thus, China avoids direct contests for control with established powers such as the EU, Russia, and the US. China and Russia have jointly vetoed seven draft UN Security Council resolutions on the Syrian war, but Beijing has refrained from forging a full alliance with Moscow. Unlike Moscow, Beijing does not establish military bases in conflict zones. Nor does it seek to establish a sphere of influence in MENA. China feels comfortable with its independent policy in MENA. It believes that other powers should abandon what it sees as their cold war mentality to establish a new security order based on burden-sharing and public goods, thereby promoting sustainable peace and development.

Since it seeks partnerships with other powers, China is likely to strengthen its cooperation with the EU in seeking to de-escalate conflicts in Israel-Palestine, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, and to address the Iranian nuclear issue. Both China and the EU emphasise the need to stick to the Iran nuclear deal; support the two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict; back a political resolution, and oppose any power’s attempt to dominate security affairs, in the Syrian war; and underscore the central role they believe the UN should play in resolving the Libyan and Yemeni conflicts. For years to come, China’s BRI and European powers’ economic investments will provide the kind of development assistance to MENA countries that is conducive to regional peace and stability. The two sides will form a partnership to solve MENA refugee issues.

Because the established powers have lost some of their interest in MENA affairs, China does not think it will be able to maintain its low-key approach to the region for much longer. Thus, it will explore channels to defend its commercial interest and construct congenial and cooperative great power relationships in MENA. China’s position on the region may shift a great deal more in the years to come.

‚China’s Great Game in the Middle East‘ – Policy Brief by Camille Lons, Jonathan Fulton, Degang Sun and Naser Al-Tamimi – European Council on Foreign Relations / ECFR.

The Policy Brief can be downloaded here